A strong, actionable theory of change (ToC) can facilitate effective programs and strong monitoring frameworks. When working on ToCs for our clients’ programs, we at IDInsight believe it is important to co-create with the teams designing or running the program. For those who are unfamiliar with ToCs, developing them can seem like a heavily technical exercise that is detached from the heart of their work and the people they work with. This is a result we especially want to avoid when doing social impact work. During our recent collaboration with the Senegalese menstrual health program Changeons Les Regles (CLR), we used visual storytelling to help a team of NGOs and social enterprises base their ToC in the human experience of their program, drawing on tenets of human-centered product design.

In this post, we share how we conceptualized, developed, and presented Binta, a character representing CLR’s target user. In centering Binta in our ToC development process, we were able to anchor CLR’s ToC in the specific activities of the program and how a user might actually experience them. We additionally discuss the supplementary visual tools we used to finalize the ToC. Finally, we share how the ToC has become a practical program design tool.

About Changeons Les Règles

In Senegal, young women and girls often have limited access to information about menstruation and menstrual health, largely due to social taboos. This can lead to difficulty understanding and managing their periods, issues with self-esteem, and reproductive health problems. Started by the social enterprise ApiAfrique in 2017, Changeons Les Règles aims to respond to these challenges by providing young Senegalese women and girls reliable information on menstruation.

Recently, ApiAfrique partnered with IT4LIFE to scale-up the initiative and provide menstrual information to more young women and girls. The plan centers the development of WeerWi, a mobile application that will include a menstrual cycle tracker, a digital library of educational content, an anonymous chatbot, and an e-shop. The app will be deployed alongside non-digital tools such as a printed guide book, in-person workshops, and a hotline operated by DKT International, where people will be able to connect with skilled midwives for menstrual and reproductive health information. Funded by Fondation Botnar as 2020 Fit for the future grantees, IT4LIFE and ApiAfrique have teamed up with Dakar Institute of Technology, YUX and IDinsight to design the program and develop these new tools.

Conceiving Our Storytelling Approach

At the start of our engagement with CLR, the program had a broad idea of its goals. The initial ToC had five UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) as aims and three levels of influence (individual, communal and institutional). With new support from Fondation Botnar, IDinsight was brought onto the CLR team to help define concrete, evidence-grounded, achievable objectives for the program. Our work included a literature review, a refined theory of change developed through collaborative workshops, and a monitoring framework.

The first step on our journey to define CLR’s outcomes was a literature review assessing menstrual health interventions. Overall, the review found that programs targeting young women and girls generally have positive impacts on the individual level, with less conclusive evidence about impacts on the community level. This indicated that CLR might not achieve its community and institutional level outcomes without adding specific activities designed to effect change on these levels. However, the literature did not present any strong conclusions on app-based menstrual health and cycle management programs. We needed a more creative approach to refine concrete feasible outcomes with CLR.

We decided to use our two workshops to focus on the “journey” of a typical app user to hone in on what WeerWi was best positioned to achieve. However, instead of discussing this journey in the abstract terms of an arbitrary unnamed “user” and their “community,” we wanted to bring this user to life to encourage more contextual and human thinking, especially given CLR’s interest in behavioral changes. Thus, we started our storytelling approach1.

Bringing Binta to Life

Enter, Binta!

Binta represents CLR’s target app user: a 15-year-old Senegalese girl who has recently experienced her first period and wants to learn more about her menstrual cycle. We follow her user journey, from the moment she finds out about the app, all the way to changes in her attitudes and behaviors, stopping along the way to consider the risks and assumptions on each page of her story.

We brought Binta and her community to life using StoryboardThat.com. StoryBoardThat offers a variety of backgrounds to allow for a wide range of stories, but there is a major limitation: nearly all of the backgrounds are based in the Western world. If you want to create a non-Western setting, you will have to think creatively about how to use the customization options on the website. For our team, this meant not using backgrounds in deserts or villages, as these are not representative of Dakar’s landscape. We experimented with color options and layering to settle on a background comparable to a Dakar street to introduce our friend, Binta.

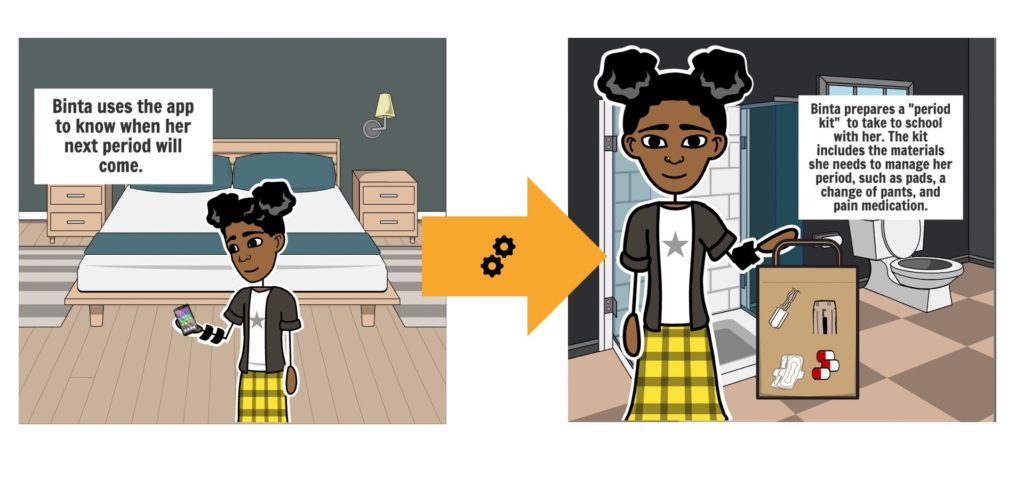

Once we settled on the background, we used StoryboardThat’s avatar feature to bring Binta to life. Avatars are customizable by skin tone, age, clothing and hair color, so it is possible to create characters representative of a variety of stories and contexts. We then built out our scenarios by adding captions, dialogue, and additional characters in Binta’s community.

Binta’s Big Break

When we introduced Binta during the first workshop, our colleagues at CLR were pleasantly surprised to see a bright-eyed cartoon-like character to break through the technical jargon that often accompanies ToC development. As we worked through the scenarios we developed, CLR indicated that Binta challenged them to really return to the user, focusing on the human side of their program. As the workshop progressed, we were able to use Binta to encourage logical thinking about how information in the app might translate into actual changes in behavior. This allowed CLR to focus on the users and what would need to happen for them to turn the information they receive into actual changes in attitudes and behaviors.

Kathleen Chau, CLR Project Director at IT4LIFE, indicated that these storyboards facilitated their understanding of the challenges an actual user might experience. “Being able to put yourself in someone else’s shoes made it easier to imagine more clearly some of the facilitators and barriers that could influence a young girl’s menstrual health, as well as her use of an app, especially one for menstrual health awareness,” Ms. Chau said. We were able to achieve this by using scenarios like the below example, in which we asked CLR to articulate what needs to happen in-between these two snapshots.

Soukeyna Ouedraogo, CLR Program Manager at ApiAfrique echoed this point, saying that Binta helped them “demystify” the typical ToC language of “outcomes” and “assumptions” by showing them how these concepts might actually manifest in the daily lives of the actual users of their program.

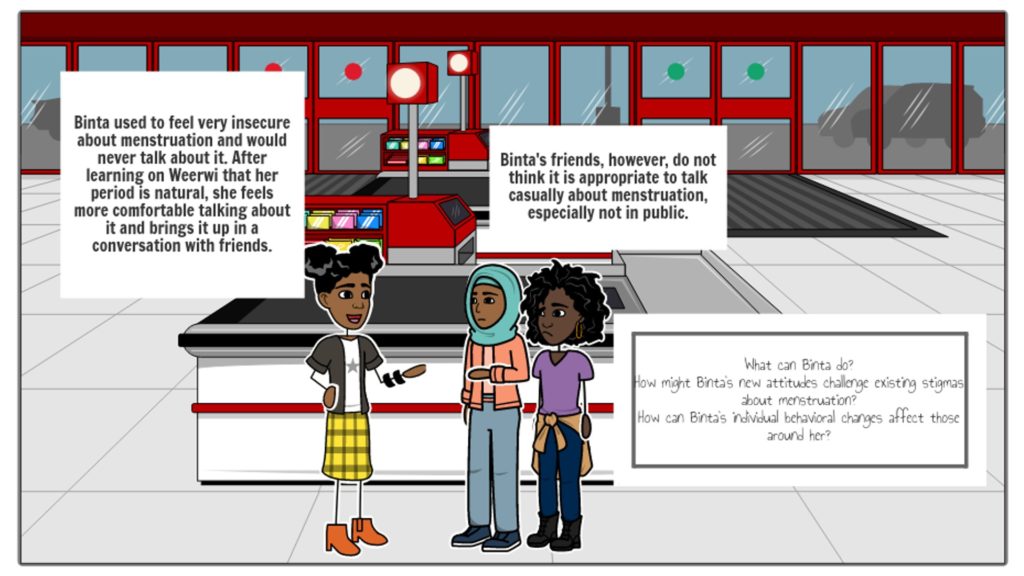

We additionally prepared scenarios with other members of Binta’s community to encourage intentional thinking about assumptions and risks associated with these outcomes. These scenarios included non-user “personas”, such as Binta’s friends and family members. Ms. Chau shared that these scenarios helped them identify the socioecological factors that would influence their work— not only those internal to the young girl herself, but also her surroundings, including her family and friends.

For example, CLR was initially hoping to reduce community-level stigmatization of menstruation. We presented a scenario to CLR to problematize that outcome, and by the next workshop, we all aligned on the fact that the app alone was likely insufficient to achieve it. “Working through Binta’s scenarios helped us to refine the expectations for what we could achieve through an app.” Ms. Chau additionally indicated that following Binta’s storyboards, CLR understood that digital tools alone can realistically only achieve certain outcomes.

Tying Up Loose Ends: Categorization by Control and Building Pathways

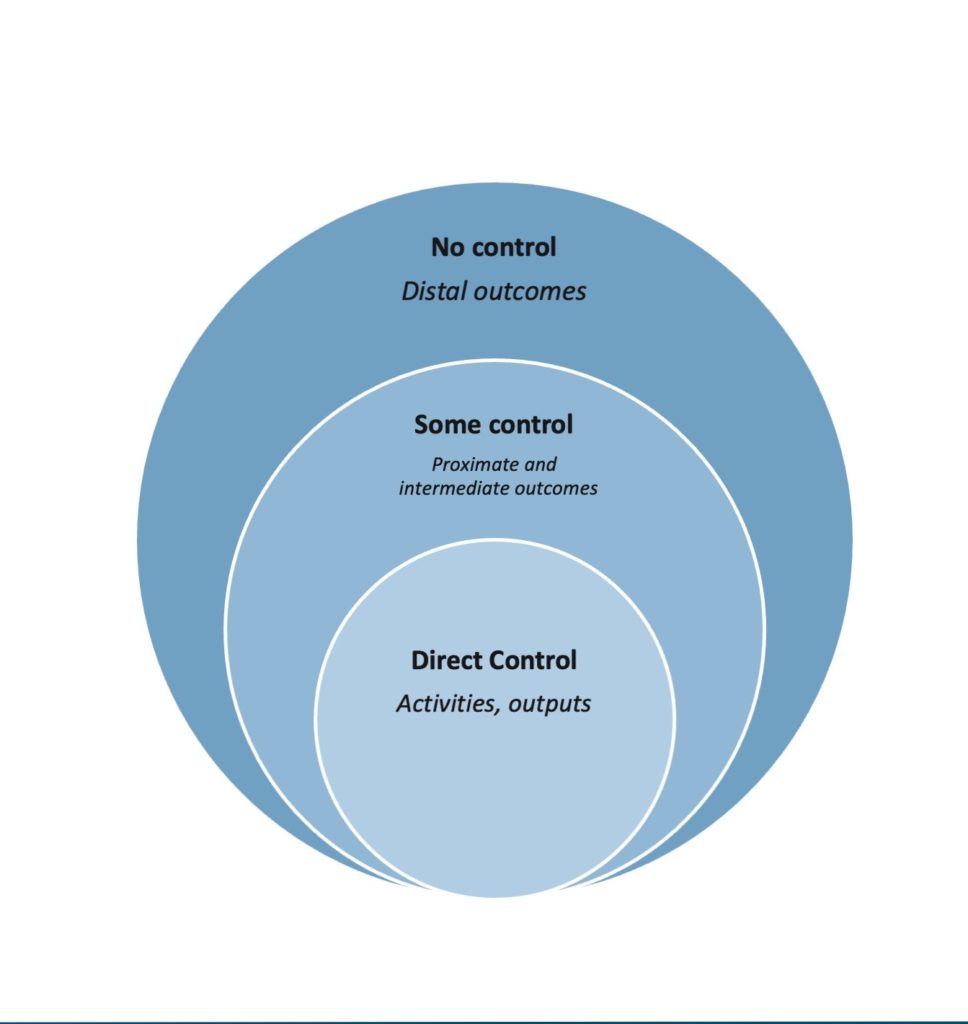

During the second workshop, we employed a categorization system and pathways activity to support CLR in focusing on the outcomes that seemed most appropriate as measures of success. The categorization system separated outcomes into three “buckets”: proximate, intermediate, and distal. Categorization was determined by the level of control that CLR and/or program participants (in this case, WeerWi users like Binta) had over affecting these outcomes.

For proximate outcomes, program activities had at least some control and program participants likely had direct control. An example of this is knowledge acquisition, such as knowledge of menstruation and its anatomy. CLR has some control over this, as they aim to provide credible, externally verified information in the app, website and booklet. Users have direct control over internalizing that information into knowledge, making this a proximate outcome.

For intermediate outcomes, CLR activities have little control and program participants have some (but not necessarily direct) control. Consider users’ procurement of quality menstrual products, for example. CLR can provide access to the e-shop, but most of the factors that determine whether or not users purchase quality menstrual products is out of CLR’s control. Users have control over their attempts to procure menstrual products, but factors such as availability in their community and financial means to purchase products are mostly out of their control.

For distal outcomes, neither program activities nor program participants have much control, if any. Reducing community stigmatization of periods is a good example of a distal outcome, as WeerWi alone has no control over this outcome, and users have little control on an individual level, even if they attempt small changes with people who are close to them. We facilitated an interactive activity to help the team categorize their outcomes along these lines. Following this activity, we could reconsider some of CLR’s ToC commitments to distal outcomes.

This activity encouraged CLR to focus on areas where they have the most influence. While this remains an ongoing process for CLR, the activity was good for initiating those conversations. Regarding other community-based outcomes, CLR said, “[it’s not that] these other outcomes aren’t important and that we shouldn’t be engaging in those, but instead indicated that we first had to have a coherent approach to the creation, development and launching of the digital tool in particular. This methodology in general helped us to have some preliminary framing around that.”

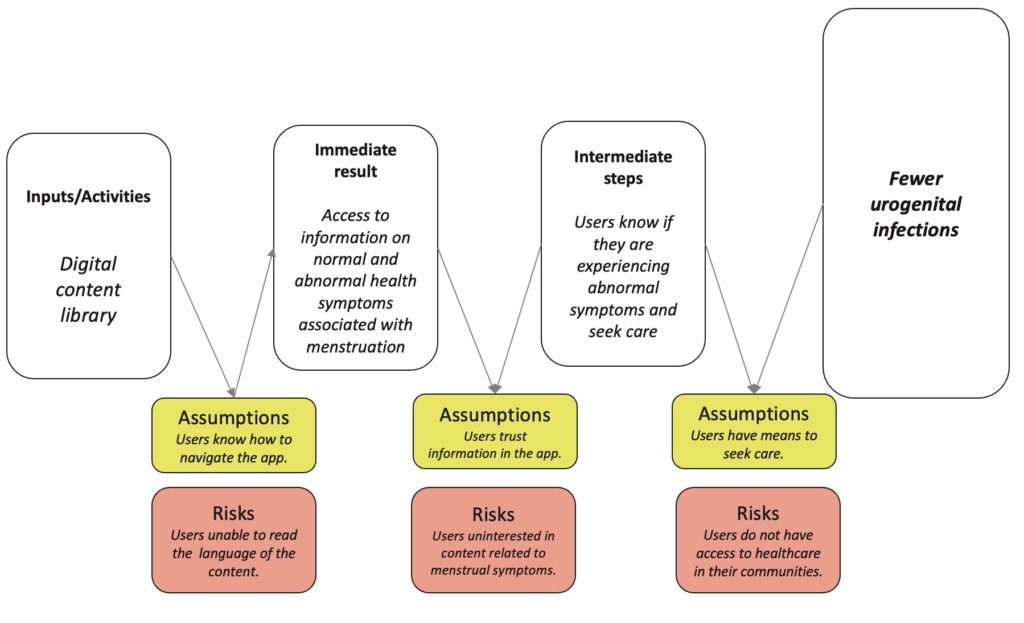

To reshift focus onto proximate and intermediate outcomes, we completed a pathways activity, where the idea was to very roughly fill in the steps, assumptions, and risks leading from a given activity to a final outcome similar to the diagram below..

Using an Actionable ToC to Support Program Design

Following these activities, we were able to narrow down intended outcomes with the CLR team. By using Binta’s story as a starting point, and using a myriad of visual tools, we were able to transform CLR’s plan from one containing many long-term visionary outcomes to one focusing on three specific goals: effective management of the menstrual cycle, autonomy & agency, and overall well-being2. Once the program outcomes and pathways were clearly defined, we were able to develop an actionable, specific and realizable theory of change diagram that CLR was able to use to support their program refinement.

The CLR team shared that workshop activities were helpful for separating direct program outputs from broader outcome areas, and this in turn helped them to develop a strategic overview of what the program could actually achieve. CLR additionally communicated that this key workshop takeaway helped them think about the main functions and features that needed to be in the app so they could achieve their desired outcomes. Ms. Ouedraogo stressed that the ToC helped them understand that each and every activity should have a purpose related to the desired end goals of the program. They revisited the app features with this in mind. They realized that some of the app features were in fact not meeting this criterion. As a result, CLR has decided to reimagine these features and consider how they can be improved to better serve the young Senegalese women and girls they want to reach.

Finally, the workshops were a useful tool for prepping the CLR team for YUX’s human centered-design work, providing a strong design skeleton. As an example, CLR was able to test critical assumptions prior to program launch by including them in YUX’s user tests, a design advantage that would have otherwise been impossible.

Conclusion – “Binta’s Bright Future”

Overall, this aspect of our collaboration with CLR was a meaningful learning experience. It allowed us to understand how persona-based design might be employed in the world of social impact, program design support, and monitoring and evaluation. We additionally learned that the possibilities of persona-based program development go well beyond product design and even ToC development. For evaluators, a storytelling tool like Binta could be a useful means for discovering the full range of program features early in an engagement, helping to diminish the likelihood of surprises later down the line.

On the other hand, program implementers like CLR might also consider using personas in the app to make their programs more engaging for potential participants. In fact, CLR is considering including a relatable avatar in the application. This could help to not only enhance user experience by providing them a relatable character, but we expect characters like Binta can actually be a very useful tool for app-based monitoring data collection. Because CLR monitoring data centers on a rather sensitive and personal topic like menstruation, it is important that users feel comfortable answering questions honestly and openly. Under different circumstances, an enumerator might be able to put a respondent at ease, but in a less traditional monitoring system like CLR’s, we expect that a relatable character like Binta might be able to replicate that same effect. CLR additionally mentioned the possibility of using Binta-like tools to consider how their work is responding to the needs of their users once launched. In any case, it’s certain we haven’t seen the last of Binta!

1While the use of visual storytelling is a rather unconventional approach to ToC development, the merits of persona-based design have been well-documented in the realm of product design and marketing research. First introduced in 1999 by Alan Cooper, persona-based design has become foundational in the human centered design field. In The Inmates Are Running the Asylum, Cooper defines persona as fictitious characters, often based on archetypes and existing ethnographic or empirical research data, that represent users (or in some cases, non-users). Cooper highlights how centering persona in product design helps us to go beyond designing interfaces and to instead focus on the needs and experiences of a targeted user and how they might engage with your program or product. Persona-based design has since become a very popular tool and is foundational to the world of user-experience design. In fact, YUX’s human-centered program design work with CLR is squarely rooted in these same concepts.

2These outcomes still represent support for the SDGs, particularly SDG 3, which is to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.”